By wpadmin

When I first entered into the world of data modeling, after several years of being a programmer and computer operator, there was a paradigm shift required to embrace the concepts behind structuring data to minimize the impact of change. The adoption of disciplined approaches to the structuring of data, including the use of third normal form, was new to our organization. We had been so used to thinking in terms of data fields and performing operations on them we had never really given any thought to the overall structure and relationships within the data. We were not alone in making this transition.

To this day developers in many organizations still focus on the data needs of their code with little or no focus on structuring data to minimize the impact of change or its use for other business processes. A useful technique for overcoming some of the challenges presented by this developer perspective is to suggest organizations think about data as it exists in the real world, beyond the immediate task at hand, as they design the data structures for their applications. This has proven to be an effective way to influence organizations towards adopting more sustainable and stable data structures for their organizations. Through my experience it seems many still have not embraced the shift to structuring data from an enterprise perspective.

Why is this? My belief is that the root cause lies with the focus of the application developer. Most people involved in information systems development begin their careers as programmers. Typically, this position entails sitting in relative isolation, receiving some program specifications from a business analyst (BA), or in some iterative fashion with a BA, and ending up with a requirement to develop code to satisfy the specification – and doing so in just a few days. So, the programmer knows he/she has a deadline to meet, yet they want their job to be interesting and challenging. The programmer can’t make the activity too interesting or challenging or they will miss their deadline, so they revert to their core competency, which is programming. As a result, the programmer develops their bit of code in the most creative way they can to exhibit their talent. There is no incentive for the programmer to properly define the fuel of their code (data), as this is outside of the scope of their assignment. The programmer (and the supervisor/manager) is interested in getting the fuel they need as quickly and easily as possible so they can concentrate on their cool code. These comments are not meant to denigrate programmers; they are based on personal experiences.

The majority of people in IT are not paid to think about data, except as fuel for coding activities. Programmers aren’t interested in sitting down with a data architect who has a PhD and debating what defines a customer for the enterprise. They are interested in writing code. The data architect, if there is one, is pressured by the BA and programmer to deliver a design as fast as possible and often with no direct business involvement.

This lack of a data focus is a cause for concern for two reasons. First: most people in IT aren’t concerned about data; this lack of concern makes the job of a data professional challenging for their whole career. Addressing this challenge will be a subject of future articles. The second point is that most data architects start out their careers as programmers and evolve into their data architect role over several years or decades. There aren’t many enterprise data architect roles. By definition there should be one individual who truly has that responsibility for any enterprise. The enterprise architect may have many data architects supporting him or her in this capacity but these individuals have a more limited scope of responsibility, usually a subject or functional area within the enterprise.

So what impact does this have on enterprise information management? The point here is that you have a lot of developers who aren’t really concerned about data and that most data architects are junior data architects (less experienced and often lacking formal training), and who have transitioned into their role from being a developer where they learned bad data habits. What is meant by bad data habits is the inclination to focus locally (a program or application view) when defining the data and to not separate business data from application data. These bad habits result in the representation of data based on a database that makes the job of the developer easier. The reason for this focus is multi-sided: the IT business analyst, tasked with interfacing with the real business person, writes exactly what the business person tells the analyst they need. The business person also presents a local view of the data, since that is what they need to perform their specific business process. So the data architect – between the developer and the business analysts – is being pressured from both sides to create a data definition that is expedient from a development point of view and one that the business analysts can relate to. Therefore, the data model usually represents the physical / application view of the data and not the normalized, enterprise / business view of the data.

So what’s wrong with that? The data representation does not reflect how the data exists in the real world, but how it is being used in an IT application. Taking an enterprise information management perspective may expose the problems this lack of real world focus on data will lead to. Let’s start with a simple example for a municipal government and examine a data model produced for a rudimentary purchase process.

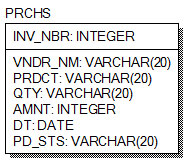

This table is a record of a purchase keyed by invoice number. It tells us who the vendor is, what product was purchased, how much of it was sold, what it cost, when it was purchased and the payment status. Most developers would be happy with this simple table, as it is easy to code to and doesn’t require any joins to other tables. The business analysts can understand it easily so there are no issues for development and presentation. The code is developed and put in production and everybody is happy.

But, a couple of weeks later, an invoice is received and can’t be entered because it has the same invoice number as a record already in the database.

So what happens now? The angry business process owner calls the business analyst and insists that the process be fixed immediately. This insistence on an immediate solution precludes any lasting resolution to the problem. The business process analyst figures out a quick, cheap, simple solution to the problem. They change the documentation to tell people to add a sequence number to the end of the invoice number when they enter it, if there is a conflict, to circumvent the unique key constraint. Everybody is happy again.

What happens next? The director of procurement decides they’d like to know how much chlorine they’re buying to maintain the city’s swimming pools because they’d like to look into getting a better deal by consolidating their purchases. So IT is asked for a report to discover how much chlorine is being purchased and from what vendors. Can this be figured out from the table structure above? Probably not. Why? First, there are no standard vendor names. The values in this field are whatever was keyed in for each invoice, therefore “Andy’s Pool Corporation” may appear as “Andy’s”, “Andy Pool”, “A’s Pool on Poplar”, Andy Corp” etc. The product may contain “Weber 3 Tabs”, “Splashes 1.25lb”, “Blue Wave Shock”. The Quantity may contain 2kg, 50lbs, 100 etc.

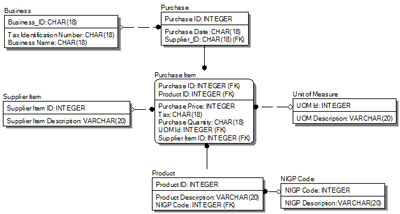

How could these problems be avoided? A good data architect models information required to drive business processes as it exists in the real world. This concept means that the data model is based on its inherent data characteristics, independent of the business process or, even worse, the program that is being developed to automate the process. In this example the analyst should have modeled the following tables (caveat: This is for illustrative purposes only it is not necessarily a completely accurate model).

In this example, the Business Table contains a surrogate key assigned for uniqueness but it also contains the Tax ID number which may be used to uniquely identifying this business with other business partners outside of the organization. The data architect modeled the supplier’s (business) product catalog so the organization can effectively communicate with them. The organization standardized the products on an internal surrogate key so IT can provide consistent reporting within the organization. The analyst also modeled the products to industry standard codes, in this case the NGIP Code (National Institute of Government Procurement), so the organization can communicate effectively with other external organizations that follow this standard. The analyst also addressed the issue of relying on the suppliers’ invoice number to uniquely identify our purchases and created a cross reference to their numbers to communicate with them.

To summarize adopting a “real world” approach provides many benefits. The organization can implement stable data structures that can be used to support all operational business processes effectively, as well as provid internal and external reporting and communications requirements for today and in the future. These goals were accomplished by looking beyond the immediate task at hand and consider the who, what, where and when of the data, from a broad usage perspective. By defining it, as much as possible, and based on the attributes and relationships that exist outside of the enterprise, we will achieve stability and reusability of this information for the organization.

About the Author