Iterative and Narrative Data: Common Ground?

By

In the first article in this series (featured in Real World Decision Support, January 2004,http://www.ewsolutions.com/newsletter/122/12201.htm, we introduced the term iterative data to mean what is commonly labeled “structured data”, and the term narrative data to mean what is commonly referred to as “unstructured data”. The reasoning behind this terminological distinction is that whereas iterative data forms a record of iterative events, narrative data tells a story. We also reported earlier that new techniques and technologies for integrating narrative and iterative data are beginning to present significant opportunities for many types of enterprise applications. In this installment we’ll examine the iterative/narrative divide from two different perspectives. At a high level, we’ll look at how these types of data have historically been managed by divergent software applications, and at a more detailed, “data model” level, we’ll begin to examing the fundamental differences and similarities between iterative and narrative data.

Iterative and Narrative Data Applications

For better or worse, the form of an enterprise’s data–and its corresponding meta data–is usually tightly coupled with the type of software in which it is implemented. If data requirements are addressed by technology specific to iterative data, the data is probably relational and the meta data is likely in the RDBMS catalog and perhaps in an ERwin model and/or meta data repository as well. On the other hand, narrative data, and its corresponding meta-data, is likely to be bound up in document management, content management, text management or knowledge management software applications.

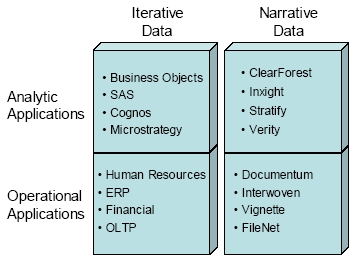

As a consequence, the data architecture of almost every enterprise implements an iterative/narrative data divide, rather than supporting integrated narrative/iterative data. The most common architecture, with some example software applications, resembles the stovepipe configuration shown in the figure below:

Most of today’s business applications are operational applications for iterative data– ERP, HR, financial, CRM, etc., etc. Most companies, large and small, also make use of analytic applications for iterative data–everything from Excel to enterprise tools from vendors such as Business Objects and Microstrategy.

Many operational applications for narrative data began in a more specialized market– mostly in industries such as engineering, manufacturing and publishing–that require rigorous management of narrative documentation. Operational applications for narrative data typically support functions for document origination, editing, approval, versioning, distribution and access control. More common operational applications for narrative data include collaboration applications such as email.

In contrast, analytic applications for narrative data are relative newcomers. Examples of these include visualization tools that can render compelling graphical representations of the results of text mining.

So, that’s the high-level, application-portolio-management perspective. If we dig down to the “content” itself, three differences–and one crucially significant similarity–are eventually revealed.

Iterative/Narrative Data: Differences and Similarity

The most significant and obvious dissimilarity between these types of data is that the “class-instance” pattern, dutifully adhered to by iterative data, breaks down with narrative data. An instance in an iterative data set (e.g., a row) is very specifically “about” a single thing–that is, it’s a representation of a single thing in the real world. On the other hand, a narrative instance (e.g., a document) is usually about–or represents–multiple things. And even worse, what it is about is often ambiguous, varying by the observer.

The second characteristic distinguishing narrative data from iterative is the preponderance of “connecting content”. This content makes a narrative readable, by connecting together the “real” content that we’ll discuss in a minute.

The final distinction between iterative and narrative data is that of order. An iterative data set such as a relational table is ideally (and some would assert, by definition) an unordered set. The order of the columns in a row is insignificant as well. On the other hand, a document has a narrative order–a beginning, middle and end. Remove the order from a narrative instance–“shred” or “normalize” it to extract and group its contained assertions by class–and it’s essentially destroyed. Ever try to read a book backwards? As a result, a narrative instance, taken as is, yields easily to only one type of retrieval: sequential. Its order provides a crucial difference between the totality of a narrative and the sum of its parts.

What then, if anything, do these data types actually have in common? The good news is that both iterative and narrative data sets contain assertions: declarations of facts. The differences are “only” in how the assertions are treated. In an iterative data collection (e.g., a relation) all assertions

-

relate to instances of the same class

-

contain properties which are arranged in the same order in each instance (although, as Dr. Codd tells us, this order is insignificant)

-

do not contain any explicit connecting content. In contrast, the assertions contained in a narrative data collection

-

may relate to instances of many classes

-

most likely are separated by connecting content

-

are probably arranged in the order required to be readable.

The underlying assertion (pun intended) of this article is that a common syntax canindeed be derived for assertions, whether arranged iteratively or narratively, and that meta data is the crucial enabler for this derivation. But before this can happen, common ground must first be found for disparate meta data.