Data architecture is an essential component and function of all successful organizations. What is “data architecture,” and why is it valuable?

A popular credit card commercial asks, “What’s in YOUR wallet?” Perhaps a similar question can be posed to data architects – “What’s in YOUR data architecture?”

“Architecture” may be the most widely used term in the field of information technology, and probably also the term with the greatest number of different connotations. Even when the focus is limited to “data architecture,” what does that really mean? Ask three data architects what they mean by the term “data architecture.” and one is likely to get four or five different answers! Much like the three blind men who each mistook an elephant for something quite different depending on what part they were holding, perspectives on data architecture differ widely depending on issues and needs. When someone refers to their “data architecture,” what are they describing? What is the role of data architecture in enterprise data management?

Examining “Architecture”

Start by looking outside the information technology field. Paraphrasing the definitions for architecture published in several dictionaries, identifies two general definitions of architecture. First, architecture is “the art and discipline of designing buildings” — architecture is a skill, a field of study and a profession. The second general meaning is more pertinent for this discussion. Architecture may be defined as “the design of any complex object or system.”

Architecture is design created to help manage complexity. People create architecture for complex things, such as buildings, music, literature, machines, organizations and systems. In each case, architecture is an organized abstraction of the system, not the system itself in its complex entirety. The principles and activities of architecture help build, understand, and control complex things.

Architecture exists at many levels. City planners design zoning plans and work with developers to design streets, lots and utility services. Architects work with homeowners to design individual homes. There is architecture in the plumbing and wiring within the home, and inside the computer chips that operate home appliances. At each level, standards and protocols help ensure components function together as a whole. Architecture includes standards and how they are applied to meet specific design needs.

Another paraphrased definition for architecture might be “an organized arrangement of component elements to optimize function, performance, feasibility, cost and/or aesthetics.” Architecture helps attain goals. Simple things do not require architecture, but architecture is essential to meet complex requirements and constraints.

Enterprise Architecture

The primary goals of enterprise architecture are to:

1) Align resources and investments with business strategy

2) To integrate resources to more effectively achieve business goals

3) Help manage change

The Zachman Framework for Enterprise Architecture and other architectural frameworks give ways to think about systems and architecture. When John Zachman first conceived the Zachman Framework, he saw that no single diagram or model could completely represent a complex system. Different stakeholders had different views. Even for a given stakeholder, different abstract views were needed to describe different aspects of the system.

In virtually every architectural framework, architecture is a set of specification artifacts. John Zachman defines architecture as “the set of descriptive representations that are required in order to create an object.” The artifacts represent both requirements specifications and the creative design response to these requirements. Some artifacts may be generated from an integrated model artifact, while others are independently created.

An architect must ensure the integrity and consistency of the specifications across multiple models, diagrams and documents within the set. Architectural frameworks try to identify a comprehensive set of artifacts and the value each artifact may potentially provide. Organizations determine the artifacts they need in their architecture, and the investments they make creating them, based on their anticipated business value. Therefore, the question becomes, “Which artifacts should be in your architecture?”

The artifacts in an architecture set vary by several dimensions. Therefore, to answer that question, it is necessary to ask a series of questions about the nature and purpose of the architecture.

First, what is the organizational scope and planning horizon addressed by the architecture? “Enterprise architecture” is comprehensive in organizational scope and more long-term and strategic in outlook, while “solution architecture” supports local, short-term, tactical implementation delivery. For this discussion, “What artifacts should be in your enterprise architecture?”

Second, what implementation is being described? Most enterprise architecture is a “target” architecture describing a “to be” state. Many organizations consider specifications about current systems as their “as is” architecture. Some organizations adopt an ideal “reference” architecture which they never expect to implement fully. Some organizations define “transition” architecture describing one or more interim states between the current and target architecture. While each implementation has significant business value, the target architecture is always the primary focus, providing the most value and providing the context for other states. Again, limit the question to, “What specification artifacts should be in your target enterprise architecture?”

Third, what aspects of the system are described? The Zachman Framework identifies six aspects: Data, Function, Network, Time, Organization and Goal.

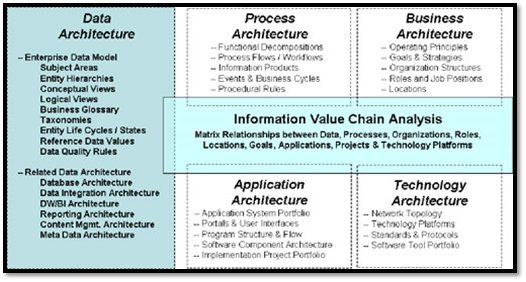

In practice, enterprise architecture typically includes data, process, application, technology, and business architecture. The business architecture (or “operating model”) may include goals, strategies, principles, projects, roles and organizational structures. The process architecture typically looks at processes (functions, activities, tasks, steps, flow, products) and events (triggers, cycles). The application architecture may include macro-level architecture across the entire application portfolio as well as the micro-level application component architecture governing the design of components and interfaces, such as a service-oriented architecture (SOA). Enterprise architecture includes all these aspects.

The question has been refined to “What artifacts should be in your target enterprise data architecture, so our artifacts will be limited to only those describing data and information (data in context)?” The answer to this question may include several different artifacts.

Enterprise Data Architecture

Experts define enterprise data architecture as an integrated set of specification artifacts that express strategic data requirements, guide integration of data assets and align data investments with business strategy. Enterprise data architecture is the subset of enterprise architecture, and includes those artifacts describing data and information.

The “primitive” models identified by the Zachman Framework focus on just one aspect of a system, describing how data relates to other data. Architecture also defines how different aspects of a system relate to each other. These relationships are critical to how any system works, especially in a complex enterprise.

“Composite” models describe the important relationships between system aspects. There is significant business value in specifying these relationships. The same business benefits derived from specifying primitive models – managing change, for instance – also justify the specification of composite models. In fact, alignment with business strategy is provided primarily through composite models. No enterprise architecture is truly complete without some defining the integration between data, process, goals, organization, applications and technology. The primary technique to define these relationships is called information value chain analysis, and its primary deliverables are matrix. A CRUD matrix (create, read, update, delete) is one example of an information value chain analysis artifact. Data architecture includes both the primitive and composite models relating to data. Of course, these same composite models will also be part of other aspects of architecture (particularly process, organization, application).

One might argue that any process/data flow diagram is a composite model. Others may point out that application architecture seems to provide a “designer” or “builder” view of an “owner’s” business process model. Since its introduction, the Zachman Framework has sparked countless such valuable continuing discussions about the nature of architecture. Regardless, no one can dispute the business value of including process/data flow diagrams in the set of enterprise architecture artifacts. Ultimately, the proven business value of each artifact determines which artifacts are created and maintained.

Categories of Enterprise Data Architecture Artifacts

There are three major categories of artifacts in enterprise data architecture:

1) The core of any enterprise data architecture is an integrated enterprise data model. Usually presented in layers, the enterprise data model defines subject areas, business entities, and business relationships. An enterprise data model may also include essential data attributes, data stewardship assignments, data quality requirements and reference data values.

2) A set of “information value chain analysis” matrices identifies the relationships between data and processes, roles, organizations and applications. Further analysis may also trace the source lineage of essential data found in information products through their related processes.

3) Various forms of data delivery architecture, such as database architecture, data integration architecture, data warehousing / business intelligence architecture, report format and distribution architecture, information content management architecture (including taxonomies) and metadata management architecture.

The diagram below identifies some of the component artifacts commonly found within enterprise architecture.

Figure 1. Enterprise Architecture Artifacts

Conclusion

To develop and implement a robust, effective enterprise data management program, every organization needs an enterprise data architecture. Understanding the concepts and artifacts of enterprise architecture and enterprise data architecture are essential to realizing the goal of managing data and information competently across the organization.