It is important to understand the non-technical or “cognitive” dimensions of Knowledge Management, dimensions that describe the learning processes of an organization and its acquisition of knowledge

Knowledge Management (KM) is frequently described in terms associated with the IT infrastructure needed to implement solutions that facilitate KM processes such as representation, capture, assimilation, and delivery of information within an organization. It is important to understand the non-technical or “cognitive” dimensions of KM as understood by key scholars in the field. These are the dimensions that address the learning processes of an organization: how knowledge is represented in an organization versus in an IT system and how it is used by individuals and later integrated back into the organization’s repertoire of experience. The questions that arise around this type of inquiry are:

- How is knowledge represented in an organizational context?

- What is the relationship of collective knowledge to individual knowledge?

- How is knowledge captured, stored, and disseminated to members for use in an organizational context?

- How is actual experience integrated back into the organization’s culture for future reference and use?

- What is the relationship of KM to organizational learning?

What is Knowledge and Knowledge Management?

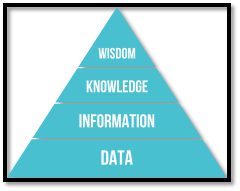

Knowledge is defined as “facts, information, and skills acquired by a person through experience or education; the theoretical or practical understanding of a subject.” Data are facts. Information is data that has been processed into a form that is meaningful to the recipient. Knowledge is what has understood and evaluated by the knower.

Knowledge management is the systematic management of an organization’s knowledge assets to create value and to address organizational requirements. Effective knowledge management consists of the initiatives, processes, strategies, and systems that sustain and enhance the storage, assessment, sharing, refinement, and creation of knowledge.

The IT Representation of Knowledge

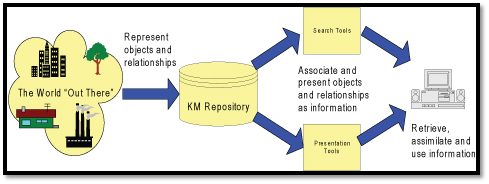

Finding a taxonomy to organize and use knowledge is one of the main challenges that KM designers encounter, especially when the domain being modeled is diffuse and lacking in structure. Objects and relationships having a real-world identity are represented in a KM Repository by a Conceptual Data Model that usually takes the form of an Entity Relationship Diagram (ERD). The IT problem for the KM solution designer is illustrated below in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Organizing and Using Knowledge

In the IT implementation of a KM solution, the cognitive process consists of end-users accessing, assimilating and using information for some aspect of their work, thus influencing its outcome. Users are constrained by the IT system’s ability to fully model or “compress” the external objects and relationships in the subject domain into a representation that the system’s tools can access and display in sufficient detail and context to assist users with their work tasks. There is also the non-technical issue of how this cognitive process scales from the individual to the organizational level so that learning becomes embedded in the group. For example, the KM solution for a customer care center might represent many aspects of the customer relationship such as purchase history, demographics, service record, complaints, and so forth. KM access and presentation tools can give service agents a complete picture of the customer’s interaction with the business over time and, in some cases, suggest new products or services to the customer and to capture their reactions to the offers. For group learning to occur, this information has to be fed back into the marketing and service / operational processes of the organization to close the loop of customer interaction. Then the organization can understand customer needs and manage its way to better products and / or services.

Representing Organizational Knowledge

In the customer care example described above, the entire process takes place at two levels of organizational knowledge: 1) a transactional level of customer interaction and, 2) a level of prediction and decision that is derived from the analysis of the interaction data. The first level is aimed at customer service agents and the second is frequently directed at managers who are in a position to redesign the processes and products of the organization to align them with the preferences that customers reveal in their interactions with the business. Presumably, managers who are empowered to reconfigure products and services do so within a larger context of the organization’s business model and founding principles. So how does an organization implement this?

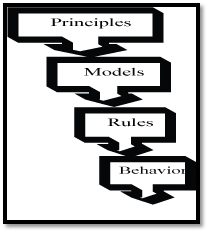

A structure that may be useful for representing organizational knowledge was developed in conjunction with the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico by Howard Sherman and is described in his book, Open Boundaries. Sherman’s structure for representing organizational knowledge (Figure 2) combines both knowledge and usage. In his structure, the level of principle represents the most abstract level at which one can speak of an organization and still make sense. The organization’s principle knowledge addresses why it exists and what it intends to do with its existence. For many companies, this is the level of purpose or mission.

Figure 2. Levels of organizational knowledge

Sherman’s next level of organizational knowledge is that of models. Models are derived from principles and represent the physical structure that the organization uses to carry out its principles.

A good example of how a business model is informed by a higher principle can be seen in the case of Southwest Airlines (NYSE: LUV). For Southwest, its point-to-point route structure, all Boeing 737 fleet, no interconnection to other airlines, and everyday low prices are part of a super-efficient business model informed by the higher organizing principle of “low fares.” Everything the airline does is aimed at reinforcing this overriding principle. Its business culture embeds this principle as anyone who has flown on Southwest can attest (even the flight officers will help to tidy up the cabin to reduce gate turnaround time). “Low fares” is the collective organizing principle that drives the Southwest Airlines business model which, in turn, drives its customer interactions through rules and employee behaviors.

Collective and Individual Knowledge

Sherman’s knowledge representation (Figure 2) also connects the individual to organizational knowledge through rules. Rules translate the principles and the business model into a procedural or transaction language that individuals can access and use to inform their behavior. In an example of the customer care system, rules are encoded in the scripts that the system presents to service agents and in the sequence of the transaction screens the agents use. Ironically, the more clearly that principles and the business model are communicated to staff, the less emphasis needs to be placed on rules as the system’s structure creates the context for appropriate behaviors. Rules/procedures are a substitute for higher-levels of knowledge that are missing, but rules are also necessary. When everyone understands the principles and the business model, the need for rules diminishes but does not go away.

An organization that is grounded in good principles and models is relatively self-organizing at the rule and behavior level; people instinctively know how to act in accordance with the higher-level organizational knowledge encoded in the principles and the business model. For example, a key performance indicator (KPI) that is chosen to measure an important organization goal can become a self-reinforcing feedback loop for employees to monitor their own behavior. British Airways discovered this when it set a KPI goal that flights could not be delayed longer than two hours, or the local gate manager had to notify the company chairman, Lord King. One can imagine the reluctance of a gate manager to call the chairman with news of a three-hour flight delay!

On the other hand, excessive emphasis on compliance to rules can bind organizations to old models and, thus, the truly innovative work is done at the “edge” by informal groups or “skunk works” that are more connected to the organization’s founding principles. A prolonged equilibrium around a set of rules that has worked well can dull an organization’s ability to sense changes and opportunities in its environment; the company becomes captive to its past success and needs a way to break out of the pattern. The classic case study of this type of break out, dating back many years is the development of various secret spy aircraft, including the U2, SR71 Blackbird, and F117 stealth fighter at the Lockheed Martin “skunk works.”

Knowledge Capture, Storage and Dissemination

So how do organizations capture, store, and disseminate knowledge to members for use (i.e., information processing)? Some scholars, such as Verna Allee, theorize that each level of knowing is associated with a corresponding mode of learning activity that links organizational knowledge to collective experience. These actions interact and provide feedback with the level of knowledge. If a situation can be resolved within the structure of existing knowledge, then it is a negative feedback situation, and the organization’s knowledge base acts like a room thermostat: it senses that something is out of balance and refers to its current knowledge base to act and resolve the situation, but there is no significant change to the knowledge base itself. On the other hand, if the situation results in the knowledge base (e.g., the rules, business model or founding principles) undergoing major change, then the organization is experiencing a positive feedback situation.

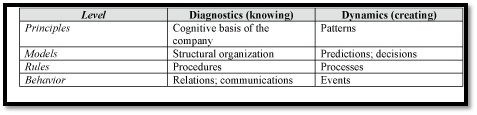

Sherman’s theory relates his organizational knowledge representation to action at different levels in the form of knowing and creating. Different levels of knowledge result in different things being created and evaluated. The format works as follows (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Sherman’s levels of knowing and creating

Figure 3 demonstrates that each level of organizational knowledge is associated with a type of knowing and a corresponding action and interaction. For example, the organizational knowledge at the principle level results in the patterns that are associated with how the organization perceives itself. Principles in action are seen as the mission and values of the organization and how these are communicated and received internally and externally. Similarly, model level knowledge begets organization structures and other arrangements that drive predictions and decisions, resulting in feedback at the model level. This was illustrated in the customer care example above when managers assimilated the results of customer receptivity to preferred offers to revise / change products and processes. Rules are expressed in the procedures that drive behavior, as in the case of the scripts presented to customer care agents.

Thus, one can say that organizational knowledge exists in levels, each level being associated with a way of knowing and acting. Organizational knowledge is stored and distributed as principles, models, and rules and ultimately results in modes of behavior that are (hopefully) in alignment with these higher level constructs. In this way, the organization’s knowledge is disseminated to the communities, internal and external, that act to fulfill its purpose.

Integrating Experience: The Learning Organization

Experience, captured as organizational knowledge, is integrated back into the organization’s collective knowing as group or organizational learning. The salient point is that integrating experience occurs at different knowledge levels, as illustrated in the table above (Figure 3). Senior managers pay attention to the financial and other outcomes that their business model creates and, when they act, it is usually at the level of the business model (e.g., dropping product lines, reconfiguring distribution, raising prices, staff cutbacks or additions, acquisitions). Founding principles change infrequently and usually do not require review, unless managers sense that the organization has drifted from its principles or that its principles are out of alignment with reality. Rules are likely to change frequently with changes in products, prices, policies, and other model-level adjustments being the most common methods.

Sometimes, managers become so embedded in their principles, business models and rules that they fail to see or respond to changes in their environment. In this case, the organization is trapped in a certain mode of thinking, and is not open to feedback and change because managers have become obsessed with one level rather than paying attention to the cognitive basis of their organization and to what their experience at all levels of interaction with the environment is telling them. One solution for this that Sherman notes is that managers should seek a “diversity of feedback.” This can take the form of outside consultants, skunk works reviews, comparison to outside industries, customer surveys, maturity model exploration, etc.; anything that offers a different view of the organization’s environment can be beneficial to the improvement of the organization’s knowledge management.

KM and Organizational Learning

A few summarizing statements can be made about the relationship between knowledge management and organizational learning. First, knowledge is not defined simply; it is complex and exists at many levels. Four levels are of a KM system would include principles, models, rules and behavior. Other approaches use differing models. Second, each level of knowing and knowledge corresponds to an appropriate activity. For example, rules drive behavior (lower level) but models affect the physical business structure and processes within which the rules apply (higher level). Learning also occurs at different levels; the feedback that happens at the event level is not likely to have much impact on principles, but it can affect the rule and model levels. Finally, organizational learning is integrated most completely as experience when the organization pays attention to all levels of its interaction with its environment. A corollary to this idea is that managers should seek a diversity of information sources by which to make decisions.

Conclusion

There is a general cognitive basis for Knowledge Management. An organization is a cognitive system, i.e., it interacts with the world at various levels, collects information about its interactions, stores this as organizational knowledge at different levels of abstraction (principles, models, rules), disseminates this knowledge to inform the behavior of its members, and tries to make sense of it all in the larger context of its founding principles, revising organizational knowledge at the appropriate level as needed.